Been a while since I last posted. It’s been a little crazy these days. Changed schedules at work, which leaves me with no real time to do many of the things I used to during the week, which pushes everything to the weekends, which then leads to having little extra time to do things like writing a blog. But I digress.

As many of you know, my novel, The Railroad Man, takes place during one hectic night on a small but busy New Jersey based freight railroad called the Midland Railroad Company. For most of you, that’s the end of that. But some of you might be saying to yourselves, “These places sound familiar to me,” while others are saying, “I know exactly where that place is!” You are all right. Because the first rule of writing is, “Write what you know about,” and since I know about a particular small, New Jersey based railroad with a legendary background that far exceeds its diminutive size, I chose it as the basis for my fictional Midland Railroad Company. That railroad was the one responsible for giving me my interest in trains and railroading at an early age as its main line ran past my house about a half-block away. It was, and still is, the New York, Susquehanna and Western. Most people around here gave it the nickname Susie-Q, obviously short for Susquehanna. Here’s the famous image of her that was designed in the 1960’s:

Kind of reminds you of that cartoon decal of Emily-D, the Midland Railroad’s mascot in my novel, doesn’t she? (Heh,heh,heh!)

Like I said in my previous post, you might notice that most of the examples of locomotives I gave are from the Susquehanna, and that was not by accident. So as the late, great Paul Harvey used to say, “Now you know the rest of the story,” or at least you will know by the time you reach the end of this blog.

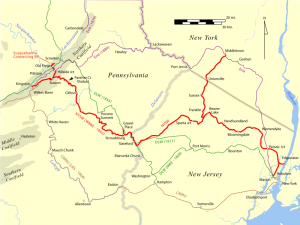

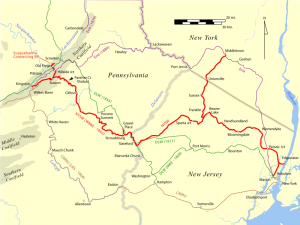

The NYSW was a small railroad that started at nearly the dawn of railroading in this country. It’s earliest corporate ancestors traced back to about 1840. It’s purpose was simple: To transport Anthracite coal from Pennsylvania to the factories in Paterson, New Jersey, which until that time received that essential fuel via the very slow and seasonal Morris Canal. After a diversionary period where the line was essentially duped into building a route to Middletown, New York, they redirected their efforts to build a line through the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania to reach the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre area and the rich Anthracite mines that dotted the region. Soon after, they built a branch line over to Edgewater, New Jersey (Then known as Undercliff) which gave them complete control of the transport process for the coal from mine to tidewater. The route map looked like this at its greatest extent, and is the mirror image of the Midland Railroad’s map as detailed in my story save for the shortening of the branch to Middletown back to Sussex:

The line became wildly successful. However, the Susquehanna soon became a victim of its own success. It was bought up by the much larger Erie Railroad, and its even more humongous financial backers on Wall Street (Chief among them being J.P. Morgan). Seems the little upstart Susquehanna upset the rates being charged for the delivery of coal to New York, forcing the companies like the Erie to lower their rates in response, which meant lower profits for them and the Wall Street robber barons who controlled them. And this couldn’t be allowed to go on. After the Susquehanna was taken over, the rate situation for coal restabilized (Rose back to their old levels) and the Eire began the systematic destruction of the smaller Susquehanna’s lines by diverting the coal business to their paralleling branch line and away from the Susquehanna. In the end, the Susquehanna’s lines were left with almost no traffic, and when the line was pulled away from the Erie’s control during the Great Depression of the 1930’s, there was little coal traffic left to maintain the over sixty miles of trackage in Pennsylvania. And so the Susquehanna abandoned everything west of the Delaware River.

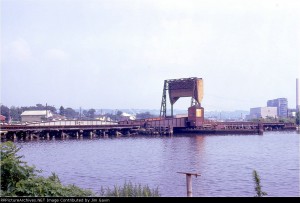

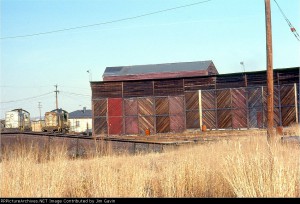

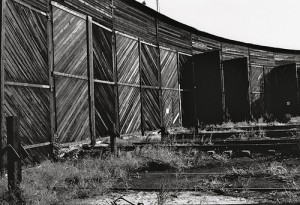

Over the next few decades, a large number of heavy industries moved in to Edgewater and the line remade itself into a merchandise carrier, but that couldn’t stem the tide of industries closing down and moving out of New Jersey as well as the diversion of traffic to trucks on the then new interstate highway system. Connections were also lost and the Susquehanna had no choice but to cut its line further and further back until it only reached as far west as Butler, New Jersey. Then came bankruptcy and what could have been the end of the line.

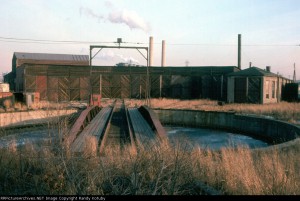

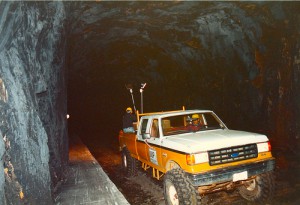

But a funny thing happened on the way to the scrap yard. The line was sold to a railfan entrepreneur named Walter Rich who saw the line as having potential for something big. Now, like Mr. Rich or hate him, he was the right person at the right time to come and save a near-floundering railroad like the Susie-Q. At that time (1980) the northeast railroad scene was in the troughs of a great bankruptcy wave, which led the government to take the bankrupt companies and combine them into the monstrosity know as Conrail. This left the New York metro area with just a single rail carrier to serve its industries, and its ports. The Susquehanna was left out of this mix. It was viewed as inconsequential, and would probably be swept up into Conrail’s dustpan sooner or later. What no one counted on was that the Susquehanna had a large, very underutilized yard in Little Ferry, New Jersey. (Actually Ridgefield, but the station was called Little Ferry for the town just across the Hackensack River. Why? I don’t really know!) The yard was close to the NJ Turnpike, and just minutes from Port Newark. And that’s where Sealand comes into the story. They were looking for a container terminal for their exclusive use to handle their then new transcontinental stack trains. Conrail would only give them a portion of their existing terminals, because after taking over five bankrupt railroads, each with an underutilized terminal or terminals in the area, they sold most of those properties off, and thus had no additional space to grow. But the Susquehanna did. And armed with a rebuilt main line and several strategic acquisitions of rail lines that Conrail had deemed surplus and was going to abandon unless someone purchased them, the Susquehanna had cobbled a route to Binghamton, New York and a connection with a railroad called the Delaware and Hudson, itself a line that was left out of the Conrail mix. The D&H was viewed as being the main competition for Conrail, being granted trackage rights to Buffalo, New York and Washington, D.C., but it was a joke. There was no way it could compete with Conrail for anything like the valuable transcontinental intermodal business. They didn’t have any terminals in New Jersey. Until now! The Susquehanna now gave them access to the largest market in the U.S., to a terminal that was completely independent of Conrail. And with the connections in Buffalo to the Chessie System (CSX’s immediate predecessor) and Norfolk and Western (NS’s immediate predecessor) there was now a new through route for container traffic to head east off the big western carriers at Chicago to New York. And the Susquehanna entered a new phase of prosperity.

For 15 years, the Susquehanna fielded as many as 4 big intermodal trains every day as well as a big general freight. But all good things must come to an end. On June 1, 1999, CSX and NS acquired Conrail and split it between themselves. At that point, neither mega-carrier needed the Susquehanna or the D&H for that matter to reach New York. They now had their own lines.

Today, the Susquehanna soldiers on, running 1 general freight train a day, eastbound one day, westbound the next, as well as switching the local industries on their line. Occasionally, CSX will route a bypass train their way when they have to, but that’s about it. Will old Susie-Q survive? I’d like to think so. It has for so many years now, longer than most of her much larger, more profitable contemporaries did, railroads with legendary names like Pennsylvania, and New York Central; Erie and Delaware, Lackawanna and Western; Lehigh Valley, Central Railroad of New Jersey, and Reading. Even New York, New Haven and Hartford. And through all the turmoil, old Susie-Q has always found some way to survive. Here’s hoping there’s something left in her tanks! Next time, I’ll bring you on a picture tour of some of the locales in my novel that are located on the Susie-Q.